April 13, 2006

Gratuitous Llama Civil War Book Review

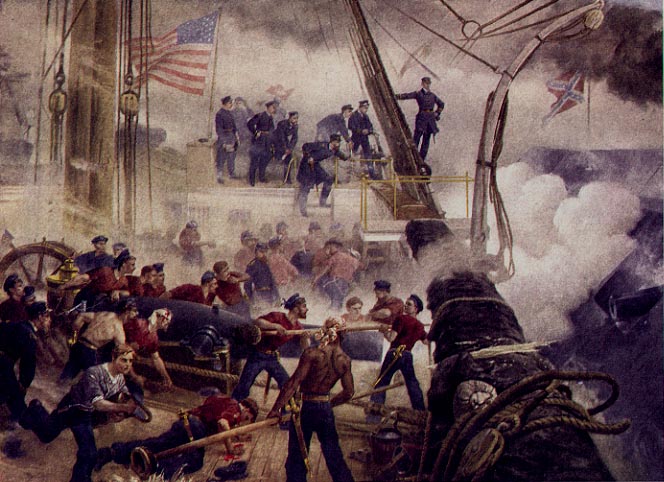

The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864: U.S.S. Hartford brushes past the Confederate ram Tennessee. Admiral Farragut is in the rigging of the Hartford at upper right.

A colleague recently recommended to me this book:

">West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay by Jack Friend.

This was the Civil War naval battle during which popular history states that Union Admiral David A. Farragut exclaimed, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" ("Torpedoes" actually meant "mines", with which the channel into Mobile Bay was liberally strewn.) Although these were not Farragut's actual words (his order was something closer to, "Go on, go on!"), the sentiment is more or less accurate. The Union monitor Tecumseh had just struck a mine and gone down with heavy losses. In order to keep his attack from stalling in the narrows opposite Fort Morgan, Farragut led a portion of his squadron straight through the mine field to continue the attack.

Let me start out by saying that this is the most comprehensive description of the battle of Mobile Bay that I have ever read. The maps and diagrams are particularly illuminating and the detail of the action is exquisite. On these grounds, I would recommend this book. Nonetheless, I have two beefs with it, one stylistic and one substantive.

The stylistic beef is that Friend has a very bad habit of repeating himself. For example, I lost count of the number of times he described the Union Fleet's preparations for battle - specifically, the striking down of superfluous yards and masts and the rigging of splinter netting and other defensive devices. Also, Friend quotes the same passage from the same letter more than once. A good editor should have caught these faults and demanded some paring.

More importantly, however, I question some of the strategic premises Fried sets out, primarily because his own narrative is not able to keep up with them. Friend contends that in the summer of 1864, with the war bogging down, Lincoln's presidency was in crisis. Grant and Sherman faced stalemate in their respective campaigns against Richmond and Atlanta and other Confederate forces - notably those in the Shenendoah Valley under Jubal Early (who famously raided the outskirts of Washington) and those to the west of the Mississippi under Kirby Smith - were free to wreak havoc. All the Confederates had to do was to hold out in the sieges of Richmond and Atlanta for a few months more, a task Lee and John Bell Hood, respectively, were undertaking masterfully, and the Union, sick and tired of the war, would have thrown Lincoln out, leaving President McClellan to sue for a negotiated peace with the Confederacy. According to Friend, the Union absolutely had to capture Mobile from the sea, thereby cutting off a critical Confederate supply line to Atlanta and also giving Sherman an out in the event that the Rebels, under Kirby Smith, were able to operate effectively in Sherman's rear.

Well. I'm sorry, but I have to file rather a lot of this under the heading Confederate Pipe Dreams. It's true that the South (and Northern Copperheads) certainly hoped this scenario would play out (and Friend is a Southerner). And it's also true that Lincoln fretted about it as late as August, 1864. But in reality, there was never much more than a very slim chance that all of these pieces could have fallen into place.

First, Friend spends a good bit of time describing the preparations for a trans-Mississippi attack in Sherman's rear by Kirby Smith. However, that attack never happened because of Union control of the Mississippi. Friend simply stops talking about it half way through the story.

Second, although Jubal Early managed to humiliate the North by burning Chambersburg and striking the outer defenses of Washington (and thereby making Lincoln the only sitting U.S. president ever to come under enemy fire), this was largely a psychological victory: nobody seriously thought Early, with his small army, could actually attack the massive fortifications of Dee Cee in earnest. Furthermore, it was not long after this raid that Phil Sheridan began his famous ride down the Shenendoah Valley, eventually crushing all remaining Confederate resistance there.

Third, Friend talks of the heroic defense of Atlanta by John Bell Hood, comparing it to Lee's masterful defense of Richmond and Petersburg. Every other history I've ever read of the war either criticizes Hood's handling of his forces or else contends that Sherman's move on Atlanta was essentially unstoppable.

Fourth, Friend seems to suggest that the seige of Richmond was an elegant trap set by Lee to immobilize the Union juggernaut. But the fact of the matter is that he was driven to it by Grant's relentless pursuit of him across Virginia in the spring and summer of 1864. Furthermore, while Friend contends that the seige was a stalemate, the truth is that Grant made slow but steady progress, gradually strangling Lee and driving him further and further into his internal lines.

Fifth, Friend's premise is undercut by the fact that although Farragut won the battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864, the Union army did not actually get around to capturing Mobile itself until April 12, 1865, three days after Lee had surrendered at Appomatox.

Finally, although Lincoln fretted about losing the 1864 election as late as early August, the fact of the matter was that the collective victories of Grant, Sherman and Sheridan radically altered the mood of the North. Furthermore, once Lincoln started actively campaigning against McClellan and his Copperhead allies, public sentiment quickly turned against the party of appeasement. (Note to Donks: pay attention to this.) When the election was finally held, it wasn't even close. Farragut's victory at Mobile Bay certainly was a psychological boost to Lincoln and to the Union in general, but I simply can't agree with Friend's apparent contention that, but for this victory, Lincoln would have lost, the North would have conceded defeat and the South would have won a negotiated settlement.

No, to me, the Battle of Mobile Bay was important for three basic reasons. First, as I have said, it was a great victory for the Union Navy, wiping out virtually the entire remaining Confederate battle fleet. Second, it closed an important blockade-running port, thereby intensifying an already critical Southern supply problem. And third, it marked the dawn of a new kind of naval warfare in that it was the first major naval battle in which iron-clads played a critical tactical part: The Confederate Fleet consisted of four ironclads. Although Farragut had a fleet of fifteen sloops and gunboats, he would not attack until he had collected four Union monitors to match against them. In this, the battle rather reminds me of the first appearance of tanks on the Western Front in World War I: clunky, crude, but terrifying in that they upset all the old military calculus.

While Friend certainly makes this point himself, I think he emphasises the strengths of these new iron monsters - the Tennessee in particular - but does not pay enough attention to their weaknesses. Most notably, although he often cites the fact that the Confederate ram Tennessee was the single most powerful vessel afloat, he skirts over the fact that she was also extremely slow and sluggish, and had inherent design problems: during the battle she passed down the entire Union line of ships but was unable to manuever into a position to effectively ram any of them. In the end, with half her gunports jammed shut and her steam drastically reduced by incessent shelling and ramming, she was simply mobbed by the Union fleet and forced to strike. Friend does everything he can to play up the threat the Tennessee posed to the Union ships and the gallantry of her crew (which was genuine), but I feel that from the beginning they were mathematically doomed. Again, I suspect this presentation is a function of what I believe to be Friend's romantic Southern bias.

And really, this bias permiates the book, not just at the strategic level I've already talked about, but at the tactical level as well. There is no denying the valor of Confederate Admiral Buchanan and General Maury who, faced with extremely limited resources, did the best they could. But the fact of the matter is that Farragut coolly and methodically built up an extremely powerful fleet and simply bulled his way into the Bay. Once he had cleared the narrows, the surrender of the Confederate forts that guarded them - Morgan, Gaines and Powell - was virtually assured. In fact, it was never really that close.

Posted by Robert at April 13, 2006 08:16 AM | TrackBackAn interesting analysis. Makes me want to find and read this book. Friend sounds like a scion of the old "glorious lost cause" school of Civil War analysis, whose basic line was that the Union won the war by a combination of brute force and pure luck. He definitely overstates the Confederacy's chances, although I have to say I wonder whether it's as extensive as you think.

My favorite account of the ACW is Catton's landmark trilogy. Catton points out that there was indeed substantial and growing antiwar sentiment during the spring and summer of 1864. Victories by Grant in the east and Sherman in the Central campaign certainly took the legs out from under the antiwar Democrat platform, but no one knows what might have happened without those victories. Yes, Grant and Sherman were making steady military progress, but Lincoln needed more. He needed politically significant victories. The press of 1864 was no more effective at reporting the real battle-line news than today's press is, and in many places the press was as overtly antiwar and anti-Lincoln as today's press is antiwar and anti-Bush, so they deliberately misled people about the war's progress. Lincoln needed victories on the order of Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga -- victories so major that no one could rationally claim the war was pointless and a negotiated peace was a better idea. Lincoln was so worried in late August 1864 that he wrote himself a private note on August 23rd, a sort of draft concession speech, saying that if he lost the election he would do his best to win the war and save the Union before the inauguration, as his opponent would certainly not do anything of the kind after the inauguration.

You wrote: "nobody seriously thought Early, with his small army, could actually attack the massive fortifications of Dee Cee in earnest. Furthermore, it was not long after this raid that Phil Sheridan began his famous ride down the Shenendoah Valley, eventually crushing all remaining Confederate resistance there."

If I recall Catton's account of this raid correctly, what got everybody's knickers in a twist was that the "massive fortifications of Dee Cee" were effectively unmanned at this time -- by order of General Grant! After the Wilderness Grant needed trained reinforcements, and there they were sitting in those fortifications, where they'd been for three years without doing any fighting at all. So he pulled them forward into his main army, and left only skeleton forces in the DC forts. That's why he had to rush to get forces back there when Early attacked. And Sheridan's victorious campaign in the Shenandoah Valley was a direct response to Early's DC raid.

"I simply can't agree with Friend's apparent contention that, but for this victory, Lincoln would have lost, the North would have conceded defeat and the South would have won a negotiated settlement."

Neither can I. But I can certainly agree with a contention that Mobile Bay plus Atlanta plus the Shenandoah Valley together effectively won the election for Lincoln, and that if none of the three victories had occurred, the election would've been a tossup at best.

Thanks for the comment. I'm a fan of Catton, too.

My point was that Friend starts out with the premise that Mobile Bay was the lynchpin to all the other actions - Atlanta, especially - and that failure by the Union to capture the city would spell serious trouble for Lincoln. But even in Friend's own analysis, neither of these suppositions plays out. While the victory was a major morale booster, it didn't have much to do with the other events.

Also, Friend speaks with an air of certainty about the strength of the anti-war movement in the North and the likely outcome of the elections had the status quo in the summer of 1864 remained unchanged. As you note, the truth of the matter is that nobody knows for sure what the dynamic would have been had the Union failed to achieve one or more of these victories.

Posted by: Robbo the LB at April 13, 2006 10:19 AMRegarding Jubal Early and Abe coming under fire: wasn't James Madison briefly exposed to British shot and shell during the 1814 assault on Washington? Purely working from memory here, but didn't he actually take charge of a battery at one point?

Posted by: Khan (No, Not That One) at April 13, 2006 01:47 PMThat, I do not know. Without having looked it up myself, my impression was that Madison cleared out pretty quick. But I'm a doofus. Steve-O would probably know better than me.

Posted by: Robbo the LB at April 13, 2006 01:59 PMYes, you are a doofus.

The things I know...

Posted by: Steve the LLamabutcher at April 13, 2006 09:57 PMSpot-on Robbo. Sadly, even with the distance of time, many of us Southerners believe total crap about the Civil War. So do some Yankees. Bottom line is that this was 140 years ago and we know how it all turned out. It does make for some interesting conversation over Scotch though.

Posted by: jay-dubya at April 14, 2006 03:00 PM

Image courtesy of the lovely and talented

Image courtesy of the lovely and talented