February 08, 2007

Gratuitous Musickal Posting

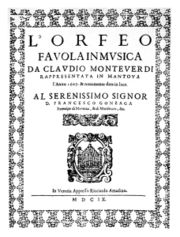

Claudio Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo, which is marking its 400th anniversary this month, is one of my very favorites. So it is with a considerable amount of trepidation that I read about a new London production being directed by Christopher Alden:

Rumour has it (Alden keeps his cards close to his chest in the interview) that the setting will be a sort of clapped-out Studio 54 disco, and if that is the case, some opera-goers are surely going to hate it.But Alden believes that "however fascinating the era in which an opera was composed may be, I have a primary responsibility to the world we live in now."

He aims to create an environment where "things are being stirred up" – an analogy to the Mantuan court of Monteverdi's day and its interest in artistic experiment.

"The fascination of Orfeo is that it looks both forward and back," he adds. "Some of it has its roots in masque and Renaissance entertainment, some of it is incredibly modern in the way it makes music serve the text.

Sigh. What he says about the opera is perfectly true - it sits right on the cusp of the late Renaissance and the early Baroque. And Mantua was a thriving, energetic hotbed of artistic creativity at the time.

But where setting the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in a gorram disco is going to get us, I fail to see. Indeed, it doesn't even make any sense - the first part of the story is pastoral, full of shepherds and maidens and worshiping the local nature gods and hey, let's go lie in the shade of that grove of trees over there. As for Orpheus' journey into the Underworld, well, most of the music at that point is quite solemn and stately and would clash bizarrely with a lighted floor and spinning, sequined ball.

But here's the sentiment that really irks me: "I have a primary responsibility to the world we live in now." That translates into a statement either that modern audiences are too stupid to understand works older than, say, Miss Saigon, or else that they are somehow above doing so, both of which I find repulsive. One of the reasons we read or listen to a Classic (he typed patiently) is the very sense of connectedness to the past that it gives us, reminding us that the matters we think about, dream about, fear, love, etc., etc., are timeless, and that the art created by past generations in approaching them is every bit as valid as what we create ourselves. Putting cheap "modern" trappings around such art simply reenforces the terribly narcissistic modern tendency to believe nothing that happened before 1960 is the remotest bit relevant to our worldview. Perhaps the real responsibility to "the world we live in now" is to remind it of this now and again.

And, of course, there is the Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty angle: Even if you don't know a single thing about Mantua in 1607 or about ancient Greek myth, you can still enjoy the wonders of Monteverdi's music and the ins and outs of Orpheus' tragic and heroic story. Slapping a Saturday Night Fever vibe on it is both ugly and distracting.

(And here's a note to Mr. Alden: An audience that doesn't "get" the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, or "get" Monteverdi's interpretation presented in a relatively straightforward style isn't going to "get" the use of a Studio 54 setting as a metaphor for the changing artistic climate of Mantua in the early 17th Century either.)

Feh.

For my own celebration, I'm going to pull out my DVD of the 2002 performance at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona by Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations and La Capella Reial de Catalunya. It's a beautiful, beautiful period performace, wonderfully sung. And you know what? I don't need a single piece of silly modernist "innovation" to understand it! (BTW, this performance is available at Netflix if you'd like to give it a try.)

UPDATE: Speaking of Netflix-available operatic performances, I recently tried out a recording of Gluck's Iphigenie en Tauride. I was particularly interested in it because Rodney Gilfrey, one of my favorite specialists in late 18th Century bass-baritone work, was singing the part of Oreste. (I have him singing the part in this excellent CD.)

What I wasn't expecting was the Attack of the Bubble-Headed Dopplegangers:

Yes, the main characters of the piece were shadowed by doubles decked out in giant paper-mache head pieces. As the principals sang, these doubles mimed their "inner thoughts." Here's an enthusiastic review of the same production done by a different cast (from which this pic is lifted). It's filled with the same relevant-to-modern-audiences bohunkus:

Without dressing the cast and chorus in Greek gowns and chitons—or decking them out in 18th century baroque versions of classic costumes—set & costume-designer Christian Schmidt has been able to update the opera's "period" visually without being untrue to the spirit of the work.A classic Greek setting and costumes—not to mention baroque—now has the quality of a Brechtian Alienation Effect. Such remote periods of style must necessarily have a distancing effect for contemporary audiences: It all happened long ago, in a place not like this one, to heroic figures who are not at all like us.

Director Claus Guth and his designer have chosen a chastely restrained 19th century look, to bring the characters and their passions closer to modern spectators. Without suggesting that Iphigenia is making human ritual sacrifices either at Wal-Mart or the First Methodist Church.

"It all happened long ago, in a place not like this one, to heroic figures who are not at all like us." Is this really what we've been reduced to? Are we really so self-centered, culturally immature and short-sighted that we can't recognize scenes of intense human emotions written about 2500 years ago and set to music 225 years ago? Or is the collective wisdom that has preserved these works for so long actually wrong about their worth? You be the judge.

And as for the Bubble-Heads?

Guth and Schmidt have borrowed both the techniques of the Bread & Puppet Theatre and the now extinct Parisian Théâtre du Grand Guignol. The Guignol used to show the most ghastly murders and tortures on stage, in full view of the audience, who came only to see such horrors, not to enjoy a good play.Four cursed members of the House of Atreus appear in this production as mute puppets—giant heads on actors' bodies. This seems a direct borrowing from Peter Schumann's Bread & Puppet Theatre, which is now having an extended run at Expo 2000 in Hannover.

Only two of these puppet-characters are actually in Gluck's opera.

Iphigenia makes her entrance—moving like a zombie toward the white metal bed, stage-center—wearing one of the giant heads. On the bed, she breaks open the head to reveal her own troubled face.

Advancing toward the bed from the opposite side of the stage is the puppet-head figure of her father, King Agamemnon. On the bed, he stabs her in the heart.

Her large entourage of white-clad priestesses—with impassive upper-face masks—in this moment also receive stab-wounds over their hearts. All the women, as Iphigenia, are clad in long white Victorian dresses—high necks, long sleeves, severely styled enough for Shaker women.

Instead of the ballets so loved by Gluck's Paris audiences, Helga Letonja has devised stylized movements for the women's and men's choruses which actually heighten the power of the emotions generated by the principals.

Both Iphigenia and Orestes have their puppet-doubles. Clearly, Guth intends these as alter-egos, for they pantomime emotions and intended actions which are only thought about—not carried out—by the siblings.

It would be more exact to call these strange, sometimes menacing figures Ids, rather than alter-egos, for they seem to call up deep elemental passions beyond reason or imagination.

Emphasis added. Of course, this is absolutely necessary because it's not like the principals and chorus are actually singing about any of these matters or anything (he typed sarcastically). In fact, there is plenty of exposition about what's going on inside our players' heads. To the extent that the pantomimes of the Bubble-heads are not in Gluck's original, the director has no business inserting them now. To paraphrase our own blogging motto, "Don't like the composer's intent? Get your own damn opera!"

Finally, it should be noted that even in its own terms the conceit of this performance fails a) because half the time it is unclear exactly what the Bubble-heads are supposed to be doing and b) because they are a terrible, terrible distraction from the real story. It strikes me that if one is going to pull this kind of stunt, one should at least draw the line at having it interfere with the underlying work (unless, of course, one is more interested in stroking one's own ego than in producing a performance respectful of the original).

Again, I say Feh!

Posted by Robert at February 8, 2007 10:07 AM | TrackBack

Giant papier-mache dolls have absolute moral authority. So the war protestors tell us.

Image courtesy of the lovely and talented

Image courtesy of the lovely and talented